|

|

|

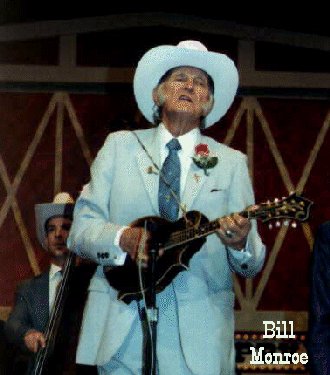

A Tribute To Bill Monroe

Bill Monroe (1911 - 1996)

Bill Monroe "the Father of Bluegrass" lives on.

But Bill Monroe, the man, has spent his last days on earth. He died on September 9, 1996, in Springfield, Tenn., at the of 84, four days short of his 85th birthday.

Much has already been written about this remarkable individual. More will be in the days and years ahead. An artistic giant, his personal creation of a distinctive genre stands as an unprecedented accomplishment in the history of American popular music.

William Smith Monroe was born on September 13, 1911, on Jerusalem Ridge near the little town of Rosine, in the hills of Ohio County, Ky. He was the youngest of eight children of James Buchanan Monroe (1857- 1928) and Malissa Vandiver Monroe (1870-1921). His father, a farmer who raised crops, mined coal, and cut timber on his land, was a fine dancer; his mother played accordion, harmonica, and fiddle. At age 10, Bill took up the mandolin. (His older, musically-inclined siblings had already laid claim to the more desired fiddle and guitar.) He got pointers on the instrument from Hubert Stringfield, who farmed on the Monroe land. Later Bill evolved his own approach, combining melody ideas from hoedown fiddling with blues guitar picking a formidable chorded rhythm chop.

Bill was occasionally lorded over by his siblings. Having poor vision and crossed eyes, he was often teased by strangers and unable to participate in many childhood activities. His vision was later corrected, but a proud desire to prove his worth - and a "lonesome" feeling that was to so characterize bluegrass - burned within him.

"I wanted a style of music of my own," he once explained. "I was going to play a different style of mandolin from other people. I was going to sing different. I was going to train my voice to sing tenor with any man."

After the deaths of his parents, Bill moved in with his uncle Jack Monroe and then with his mother's brother, trader and fiddler Pendleton Vandiver. Uncle Pen, later immortalized in a Monroe classic, had a broad repertoire of tunes and an infectious rhythm shuffle with his bow. He profoundly influenced Bill's musical development. Arnold Schultz, an African American laborer, guitarist, and fiddler, taught Bill to play the blues. Bill backed each man on guitar for dances in the region.

In 1929, Bill joined brothers Birch (1901-1982), and Charlie (1903-1975) in Whiting, Ind., where they had gone to find work. In 1930, they moved to East Chicago, Ind. Bill worked there for five years at the Sinclair oil refinery, washing and stacking barrels. He developed much of his labor-hardened strength in those days and was also exposed to new music in the city, including jazz.

The young men played at parties and dances much as they had in Rosine: Birch on fiddle, Charlie on guitar, and Bill on mandolin. Their big break came when they and a friend, Larry Moore, were noticed at a square dance by promoter Tom Owens. He hired the Monroes, their girlfriends, and Moore and his wife as an exhibition dance team with a package show from the WLS Radio "Barn Dance" program. They toured part-time and appeared at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair. The Monroes also occasionally played music on local stations during this period.

In 1934, Charlie was asked by the Texas Crystals laxative company to appear on a radio program it sponsored in Shenandoah, Ia. He invited Bill to go with him. (Birch stayed behind to work at a refinery job.) Bill and Charlie, now known as the Monroe Brothers, began performing and touring as full-time musicians. Their tight, soaring harmonies, Charlie's punctuating guitar runs, and Bill's fiery mandolin leads created a sensation and influenced generations of country music duet acts. The 60 sides they recorded for Victor Records ranged from the frolicsome "Have A Feast Here Tonight" to their greatest hit, the stirring gospel number "What Would You Give In Exchange For Your Soul?"

Personal and artistic differences broke up the act in 1938 (although in the 1950s they toured together with their bands and recreated the Monroe Brothers duet as a finale). Charlie formed Charlie Monroe's Boys and then the Kentucky Partners. Bill founded a group in Little Rock called the Kentuckians. He then moved to Atlanta and organized a new group+the Blue Grass Boys.

Bill began to forge an innovative and highly personal string band sound. Its roots were in traditional dance music and modal ballads. To these he grafted church-style harmonies, blues stylings, and a jazz-influenced improvisational format in which the fiddle and mandolin made solo statements or played backups while the guitar and bass fiddle laid down a bed of rhythm. Bill pitched songs in higher than usual keys to suit his natural tenor range and discovered that this put an extra "edge" on his music. And he insisted not only that his sidemen play with great precision but that they subtly anticipate the beat, attacking the notes in a surging timing that further energized his sound. This distinctive timing, Monroe later said, defined bluegrass long before the addition of the 5- string banjo further popularized it.

In October 1939, Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys successfully auditioned for the Grand Ole Opry on WSM radio in Nashville. Opry founder George D. Hay said, "Well, you're here, and if you ever leave, you'll have to fire yourself." Monroe was a member of that prestigious show the rest of his life, and at the time of his death held seniority on its roster. His initial hit, an uptempo version of Jimmie Rodgers' yodeling classic "Mule Skinner Blues," helped firmly establish his new music.

Several people played crucial roles in the music's development (notably Don Reno and Earl Scruggs, who excited Bill with the possibilities of North Carolina-style three-finger banjo picking). But Monroe had created something personal and truly new. Today, the word "bluegrass" is sometimes erroneously used as a generic name for centuries-old mountain music. But it is significant that the term did not come into widespread use until the mid-1950s: Bluegrass was truly Bill Monroe's invention, a modern music with traditional roots.

Although its basic elements were established with the 1939 Blue Grass Boys, there were refinements and experiments down through the years. The most significant addition was that of syncopated 5-string banjo. (Some fans hold the 1946-48 edition of the Blue Grass Boys, with Scruggs on banjo, Lester Flatt on guitar, Chubby Wise on fiddle, and Howard Watts or Birch Monroe on bass, to be the first true bluegrass band and one of the finest.) During various periods, Monroe featured trio vocals and a "Blue Grass Quartet," used twin and even triple fiddles. He briefly had accordion and/or harmonica in his band, on a few occasions recorded with piano or vibes for special effects, and did an experimental 1951 session (at the request of then-producer Owen Bradley) backed by drums and electric guitar. But overall he stayed close to the style he had perfected.

Because his vision had been so poor in childhood, Monroe was unable to take advantage of the "singing schools" organized by traveling teachers who taught the rudiments of music theory. So he had become a largely self-taught musician, working by ear. Still, each element of his music was written on the pages of his mind. He expressed his belief in precision and professionalism of performance when he talked about "playing your music right." Monroe (who considered the fiddle to be at the heart of his band sound) took special pains to teach new tunes to his fiddlers. He would play each composition on his mandolin, sing passages, even use gestures and body language, until he had communicated exactly the notes and phrasing he heard in his head.

The Blue Grass Boys recorded for Victor in October 1940, and October 1941. From February 1945, to October 1949, Monroe recorded for Columbia. He began in February 1950, with Decca (later known as MCA), with which he remained the rest of his career. During his latter years, he also appeared as a guest artist recording with friends on other labels.

Monroe prospered during the 1940s. He toured the South with his own tent show, headlined by the Blue Grass Boys but featuring a variety of entertainment: Grand Ole Opry stars such as rollicking banjoist Uncle Dave Macon and harmonica whiz DeFord Bailey, comedy acts, and even baseball. (Monroe was a passionate fan of the national pastime. He played his semi-professionals, including himself and other band members, against local teams in afternoon games before the evening stage show.)

Later, he traveled even more widely. A walkway on his property was lined with stones he collected in each of the 50 states. He performed in Europe and Japan, and during a 1983 visit to Israel was baptized anew in the River Jordan.

The 1950s, however, were a difficult decade. Interest in his style of acoustic country music withered with the rise of electrified country and western and rock-n-roll; his former sidemen Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs came to dominate general awareness of (and demand for) bluegrass with their highly successful partnership. Monroe continued to perform and record for his core following.

His career rebounded dramatically in the 1960s. Folklorist Ralph Rinzler documented Monroe's role as the true creator of bluegrass and for a while serving as his manager, successfully introduced him to the folk music revival. Monroe made his first appearance at a folk festival in 1963 at the University of Chicago. In 1965, country music promoter Carlton Haney organized the first weekend-long bluegrass festival around reunions of classic editions of the Blue Grass Boys band. Any lingering resentments Monroe had over being so widely copied now disolved as he was lauded as the father of a distinctive music. Younger generations in the United States and overseas discovered bluegrass. Monroe entered into a new popularity which thereafter never waned. "You are all my children," he would sometimes say to throngs of musicians and grassroots fans during the climax of the major June festival at his park in Bean Blossom, Brown County, Ind.

When the album "Bill Monroe And Friends" was produced in 1983, famous names of mainstream country music clamored to record with this living legend. His stature and that of bluegrass grew in Nashville in the 1980s and '90s. Veteran performers respected him, young superstars revered him. Beside frequent TV performances, he made guest appearances in country music videos and was the focus of several acclaimed documentaries.

A lifetime of creativity yielded hundreds of songs and tunes (many but not all of which were recorded.) The tribute "Uncle Pen," the affectionate "My Little Georgia Rose," the nostalgic waltz "Blue Moon Of Kentucky," the searing trio "On And On," and the showstopping instrumentals "Blue Grass Breakdown" and "Rawhide" are only a few of the Monroe compositions played by nearly every bluegrass band in the world. Even as he aged Monroe remained startlingly innovative, as witness his haunting 1981 masterpiece "My Last Days On Earth," written in C# minor tuning and recorded with choir, violins and cellos, and wind and sea bird sound effects.

Bill Monroe, of course, influenced every bluegrass performer. Many of the greats worked directly with him as Blue Grass Boys, their names are too numerous and too well-known to Bluegrass Unlimited readers to list here. But he also had a profound influence on American popular music in general.

Elvis Presley's first successful record was a 1954 uptempo version of "Blue Moon Of Kentucky." (Presley later apologized to Monroe for taking liberties with the song; but Bill encouraged his career and rerecorded the number, the first half as a waltz, the second in 4/4 time ala Elvis.) Other performers he directly influenced include rock stars Buddy Holly, Levon Helm, and Jerry Garcia; new acoustic stylist David Grisman; and country luminaries Ricky Skaggs, Keith Whitley, Vince Gill, and Marty Stuart. And many, many others. Monroe was pleased that aspiring musicians could learn the principles of music through his style, then go on to careers not only in bluegrass but folk, country, rock or jazz.

"Bluegrass really is a school of music for a lot of young people today," he once said. "Bluegrass will put you into another class of music if you want to go there."

Bill Monroe the man was truly a study in contrasts.

He exuded dignity yet possessed a wry sense of humor. He was formal but churned with deep passions. He was fun loving but disciplined, and he never smoked nor drank. He was unhurried yet had a fierce work ethic. He was as comfortable in work gloves and overalls as he was in his trademark suit, tie and Stetson. He would stand in strong, centered balance, yet he loved to dance the Kentucky back step. He would give children quarters as souvenirs and give uninformed reporters silence. He could demonstrate immense loyalty but, if offended, could hold long grudges. He was a loner, but courtly and romantic. (Many of his "true songs," both happy and sad, were inspired by love experiences.) He was a gentleman and a fighter. He could be as tender or as hard edged as his own music. Even as he mellowed, he could still be taciturn and blunt; yet he patiently nurtured many aspiring talents, was unfailingly gracious to his fans, and was characterized by Tony Conway, his agent at Buddy Lee Attractions, as a pleasure to work with because of his professionalism and utter reliability. He was forward-looking but fascinated by things that "go a way on back in time." In many ways, he was the product of an isolated 19th century society who made his mark on the great 20th century world.

As friend and former sideman Sonny Osborne put it: "When you talk about Monroe, you're talking about a different breed of human being. You've never seen anybody like him in your life, and you never will again."

His Scots heritage of big boned physical strength and stubborn determination stood him in good stead in his final years. He survived colon cancer. His trademark 1923 Gibson Lloyd Loar F-5 mandolin, which possessed an instantly recognizable timbre, was smashed by an intruder although fortunately later repaired. He underwent heart bypass surgery. He mended after a broken hip. He oversaw the sale of his beloved 288 acre farm in Goodlettsville, Tenn., which the Grand Ole Opry now owns. He met each situation with the stoutness, optimism, and sheer willpower that characterized everything he did.

His latter years also saw myriad honors. In 1969, he was made an Honorary Kentucky Colonel. In 1970, he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. In 1986, just before his 75th birthday, he was recognized by a U.S. Senate resolution lauding "his many contributions to American culture and music." He received the 1986 Award of Merit of the International Bluegrass Music Association and was inducted in 1991 into the new IBMA Hall of Honor on its inaugural ballot. In 1988, he won a Grammy award for Best Bluegrass Recording from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences for the album "Southern Flavor." He was also nominated for Grammys in 1987, 1989, and 1995. He was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) at the 1993 Grammy Awards show.

Monroe was proud of having performed at the White House for four consecutive presidents: Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and Bill Clinton. On October 5, 1995, President Clinton presented him with the National Medal of the Arts. A few weeks earlier, on September 21, he had received an honor which may have touched him equally when a bronze plaque to him was unveiled in the jamboree building in his hometown of Rosine.

During his final years of touring, he would often arrive at a show to find a crowd standing in the hot sun or pouring rain, waiting just to see him step off his bus. The doors would open. Monroe would peer out and take in the sea of eager faces. He would smile and sing the first line of his famous composition: "Blue Moon of Kentucky ..."

"... keep on shining!" the crowds would sing back without missing a beat.

And they would cheer.

Such love was the greatest reward for the lonesome little boy from Jerusalem Ridge who had grown to be quite a man. Hundreds of studio and concert recordings, and the legacies that will be passed down by those who knew him - these will continue to give him life.

So will his creation, as Bill certainly knew. "If you really watch it close, look at all of it, it makes a powerful music," he said with pride and honesty. "I have never heard any music I thought would beat it, myself."

Bill Monroe was married and divorced twice: to the late Carolyn Brown Monroe and to Della Streeter Monroe. He had two children by his first marriage. His son James (born in 1941) performed with the Blue Grass Boys and his own band, the Midnight Ramblers. His daughter Melissa (1936 1990) recorded as a vocalist in the early 1950s for Columbia.

Services were held at the Ryman Auditorium and at the Rosine Methodist church in Rosine, Ky. He was buried in Rosine, Ky., on September 12, 1996.

He is survived by James; a grandson, James Monroe, II; a sister Bertha Monroe Kurth, of Rosine (his last living sibling); and by all of us whose lives wouldn't be nearly as happy if Bill Monroe hadn't fathered the woody, wailing, wistful, high powered, high lonesome, uncompromising, and undying music called bluegrass.

Richard D. Smith

The virtual base on which the whole of bluegrass music rests, William Smith (Bill) Monroe was born at Rosine, Kentucky, on September 13, 1911, the youngest of eight children. Brother Charlie was next youngest, having been born eight years earlier. This gap, coupled with Bill's poor eyesight, inhibited the youngest son from many of the usual play activities and gave him an introverted nature which carried through into later life.

Aside from his musical family, one of Monroe's early influences was a black musician from Rosine, Arnold Schultz. Bill would gig with him and rated him a fine musician with an unrivalled feel for the blues. At this time he also started to hear gramophone records featuring such performers as Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers.

In 1934, Radio WLS in Chicago, for whom the three brothers (Birch on fiddle, Charlie on guitar, and Bill on mandolin) had been working on a semi-professional basis, offered them full-time employment. Birch decided to give up music, but Charlie and Bill reforemed as the Monroe Brothers. In 1938, they went their separate ways. Bill formed the Kentuckians and moved to Radio KARK, Atlanta Georgia, where the first of the Blue Grass Boys line-ups was evolved. Bill also began to sing lead and to take mandolin solos rather than just remaining part of the general sound. In 1939, he auditioned for the Opry and George Hay was impressed enough to sign him.

By 1945, Monroe's style had undergone several changes. Most notable was the addition of Earl Scruggs, with a driving banjo style, putting the final, distinctive seal on Monroe's bluegrass sound. Flatt and Scruggs remained with Bill until 1948. Among Monroe's best known songs from the period is "Blue Moon of Kentucky." Included here is another of Monroe's hits: "I'm Going Back to Old Kentucky."

After signing with Decca Records in 1949, Monroe teamed with Jimmy Martin, and entered into his golden age for compositions. He wrote "Uncle Pen," "Roanoke," "Scotland," "My Little Georgia Rose," "Walking In Jerusalem," and "I'm Working On a Building," the last two being religious 'message' songs, always part of the Monroe tradition from the earlier days.

Bill Monroe was elected to the Country Music Hall Of Fame in 1970. His contribution to country music is inestimable. On August 13, 1986, one month to the day before his 75th birthday, the US Senate passed a resolution recognizing "his many contributions to American culture and his many ways of helping American people enjoy themselves." It also said, "As a musician, showman, composer, and teacher, Mr. Monroe has been a cultural figure and force of signal importance in our time."

Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs pioneered a particular type of bluegrass under Bill Monroe's leadership -- especially Scruggs' "three-finger banjo" technique -- and thus helped to popularize bluegrass immensely. Both came from highly musical families. Lester's parents both played the banjo (in the old 'frailing' style) and Lest practiced on both guitar and banjo. Earl came from an area east of the Appalachians which was already using a three-finger style on the five-string banjo.

In 1943, Lester and his wife Gladys were hired by Charlie Monroe. Lester sang harmony and played mandolin. He tired of the travelling and quit, then procured a position with a North Carolina radio station. It was there that he received a telegram from Bill Monroe asking Lester to come and play with him on the Grand Ole Opry.

Earl had played with his brothers from the age of six and by 15 he was playing on a North Carolina radio station with the Carolina Wildcats. After the war, Scruggs appeared with John Miller on Radio WSM in Nashville. Miller then stopped touring and Earl, out of work, was hired by Monroe.

In 1948, within weeks of each other, Earl and Lester resigned from Monroe to escape the constant travelling (Monroe has always been a dedicated touring man). Almost inevitably the two then decided to team up and do some radio work. They recruited ex-Monroe men Jim Shumate (fiddle) and Howard Watts (a.k.a. Cedric Rainwater on bass), and then moved to Hickory, North Carolina, when the were joined by Mac Wiseman. That year, 1948, they made their first recordings for Mercury Records.

The band took its name from an old Carter Family tune, "Foggy Mountain Top," calling themselves the Foggy Mountain Boys. In 1950, they were offered a lucrative contract by Columbia Records, a recording association that was to last for 20 years. In 1953, the band began broadcasting "Martha White Biscuit Time" on WSM, a show which not only ran for years, but which saw them come into country music prominence. Flatt and Scruggs and their band became members of the Grand Ole Opry in 1955, and were winning numerous fan polls and industry awards.

They consolidated their position as leaders of the bluegrass movement and sold a vast number of records. By the end of the '60s (mainly pushed by Earl), they began experimenting with new folks songs, drums and gospel-style harmonies in an effort to build on a younger audience. Some of their older fans were unhappy about the changes, and in 1969, they split up. Lester, who died in 1979, returned to a more traditional sound, forming the Nashville Grass, composed mainly of the Foggy Mountain Boys. Earl defiantly went off in new directions with his Earl Scruggs Review. In recent years, Scruggs has cut back on his activities, while his sons have made their mark as songwriters, producers and multi-instrumentalists in country music.

Although musicians had been recording fiddle tunes (known as Old Time Music at that time) in the southern Appalachians for several years, It wasn't until August 1, 1927 in Bristol, Tennessee, that Country Music really began. There, on that day, Ralph Peer signed Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family to recording contracts for Victor Records.

These two recording acts set the tone for those to follow - Rodgers with his unique singing style and the Carters with their extensive recordings of old-time music.

Known as the "Father of Country Music," James Charles Rodgers was born in Meridian, Mississippi on September 8, 1897. Always in ill health, he became a railroad hand, until ill health caught up with him and he was forced to seek a less strenuous occupation. An amateur entertainer for many years, he became a serious performer in 1925, appearing in Johnson City, Tennessee and other places. In 1926, Rodgers and Carrie, his wife of 6 years, moved to Asheville, North Carolina, and organized the Jimmie Rodgers' Entertainers, a hillbilly band comprising Jack Pierce (guitar), Jack Grant (mandolin/banjo), Claude Grant (banjo), and Rodgers himself (banjo).

Upon hearing that Ralph Peer of Victor Records was setting up a portable recording studio in Bristol, on the Virginia-Tennessee border, the Entertainers headed in that direction. But due to a dispute within their ranks, Rodgers eventually recorded as a solo artist, selecting a sentimental ballad, "The Soldier's Sweetheart," and a lullaby, "Sleep, Baby, Sleep," as his first offerings. The record met with instant acclaim, thus causing Victor to record further Rodgers' sides throughout 1927, including the first in a set of 13, Blue Yodel # 1 (T for Texas)

(149k excerpt) (660k longer version)

Rodgers, who died in 1933, never appeared on any major radio show or even played the Grand Ole Opry during his lifetime. But he, Fred Rose, and Hank Williams were the first persons to be elected to the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1961, which is indicative of his importance in the history of Country Music.

One of the most influential groups in country music was The Carter Family (A.P., Sara, cousin Maybelle, and others). The Carters first recorded for Ralph Peer for Victor on August 1, 1927--the same day that Jimmie Rodgers cut his first sides--completing six titles, including "Single Girl, Married Girl," at a makeshift studio in Bristol, Tennessee, known as the Bristol Barn Sessions.

Sara and A.P. obtained a divorce during 1936, but continued working together in the group, which now included Anita, June, and Helen (Maybelle and Ezra Carter's three daughters) and Janette and Joe (Sara and A.P.'s children). From 1936-39, the Family cut for Decca, and after that for Columbia and again for Victor. The last session by the original Carter Family took place on October 14, 1941, and the Family disbanded in 1943, having waxed over 250 of their songs and one of their signature songs, "Sunny Side of Life" recorded in 1928. Also included is a video clip from the 1950's of Maybelle's daughters June, Helen, and Anita who carried on this legacy for more than two decades after the original Carter's left the studio.